“We have got to be as clear headed about human beings as possible, because we are still each others only hope.” - James Baldwin

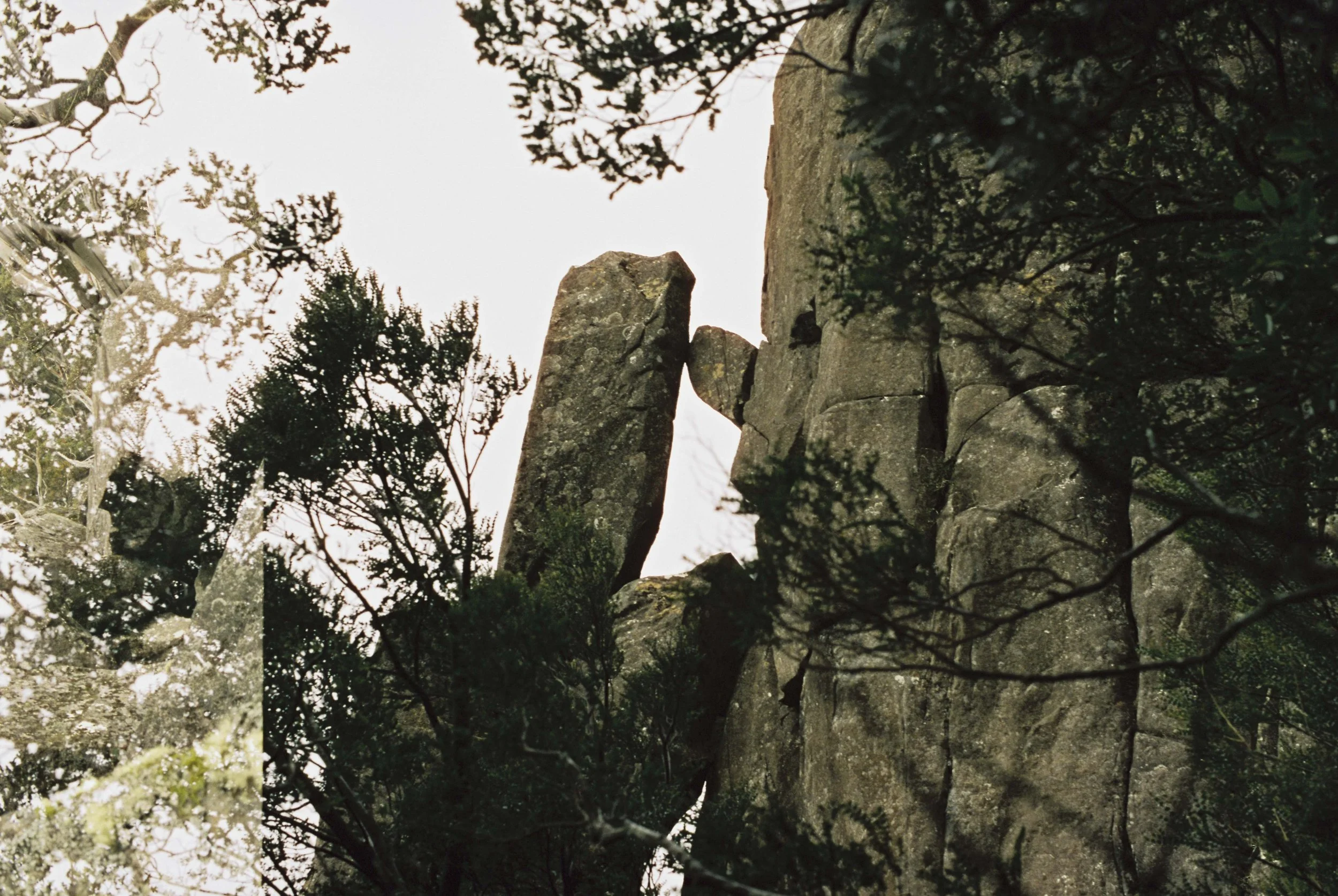

Beneath the mighty Mt Rugby. Pentax MX, Kodak Portra 800, Nov 2025

It was day eight of our trip with Gabriel Matuszak through the South-West and we had only one obstacle left before reaching our rendezvous point with Grant Dixon at Claytons Corner near Melaleuca Inlet. We had to paddle across the Bathurst Narrows!

This is the narrow channel through which all of Bathurst Harbour is drained into Port Davey at low tide. This means that the channel effectively becomes a fast flowing river that is just about impossible to paddle against in a packraft if the tide is flowing the opposite way to the intended direction of motion. The tide charts told us there would be low tide around nine o’clock in Port Davey, followed by a high tide around midday. As we found out, the tide for Port Davey isn’t necessarily accurate for what happens in the Narrows as there seems to be a fair delay; and while thankfully the tidal flow wasn’t too strong for us, it was still flowing out against us the entire time we were in the Narrows. The beauty of the surrounding country made up for the slight handicap placed against us.

We were weary after the last week of paddling the Crossing, Davey and Spring Rivers, not to mention the arduous walking in between with our giant packs. I was not able to paddle fast as my left shoulder was playing up by this point. It was a three hour paddle for us from Farrell Point to Clayton’s Corner, and we were glad to get there! It certainly felt longer than the seven kilometres indicated on the map.

What a mountain! Pentax MX, Kodak Portra 800, Nov 2025.

Clayton’s Corner is a sheltered little cove near Melaleuca Inlet. It is named after Clyde and Win, an adventurous couple who lived in Port Davey from the 1950s. There is a cute little jetty and hut built by Clyde and Win which is now looked after by Parks and Wildlife Services. While this hut is accessible from the Port Davey Track, it is mostly visited by boaters who take shelter in this nicely tucked away little bay, well sheltered from the fierce Southerlies.

The sun was finally out and we were glad to be able to hang out all our saturated gear around the hut. We had originally planned to meet Grant at Melaleuca but we were way too pooped to sign up for an additional fourteen kilometres of paddling that day. Grant was due to fly in that day in the afternoon, and he was to bring us our rations which we had left with him before we started our trip with Gabe.

We had completed the first leg of our journey and thought it wise to spend the afternoon resting before launching into the more difficult second leg following the Old River to its source, Federation Peak.

The idea for this second part of our journey was conceived by Grant, who called it an ‘elegant idea’ to follow the Old River upstream, then walk over Federation Peak and paddle the Cracroft and Huon Rivers out. Gabe and I were gullible enough to let this ‘elegant idea’ take hold of our minds.

Upon receiving the forecast a few days earlier however, we were starting to have our doubts with Gabe. It had rained five out of eight days on the first leg, and there was a lot more rain coming. In fact, there was only to be one dry day in the following week. This just about ensured we would be walking along the Old River, not paddling it, as the water levels were going to be way too high. Furthermore, the idea of lugging a fully saturated packrafting pack across the Eastern Arthurs was a daunting idea.

Golden light, winding path. Pentax MX, Kodak Portra 800, Nov 2025.

When we saw that atrocious forecast, Gabe and I realised that there was only one way we were going to survive the second leg of our journey; for it was going to be a sufferfest. We needed more chocolate than we had rationed!

Since Grant was flying in to Melaleuca, he was going to bring us our food for the following eleven days. So we said to Grant via an inreach message: “If we are to proceed, could you be as kind as to bring us two additional blocks of Whittakers chocolate?” Grant confirmed he would. With the additional chocolate rations guaranteed, the weather forecast didn’t seem so bad after all.

Grant arrived to Claytons paddling his packraft around six pm that day, with our food, gas and two extra blocks of chocolate. Despite the biblical rain forecast, it appeared that the second leg of our trip was on.

Melaleuca Inlet, Pentax MX, Kodak Portra 800, Nov 2025.

-A.S., 7/2/26, Brushy Creek.